03 – THE GREAT AMERICAN ROADTRIP

Argus is interested in receiving a variety of submissions that fall under the genres outlined below. Submissions may respond to one of the five prompts above in a variety of ways:

Essay - A text-heavy submission that may be opinionated or research-driven. Maximum of 3000 words, 0-4 supporting images

Photo Essay - A collection of photos taken by the author with optional text captions to support the author’s narrative. Maximum of 12 images

Interview - A transcript of a conversation held between the author and someone who has something to say about the Great American Roadtrip. Maximum of 3000 words, 0-2 supporting images

Travel Report - An authentic, narrative-based submission meant to communicate a personal account of the Great American Roadtrip. May include text, sketches, photos, poems, or something else. Maximum of 1000 words, 0-5 images

Project - An architectural intervention designed somewhere along the Great American Roadtrip. Submissions should include images, diagrams, and descriptions. Maximum of 8 images

Itinerary - A designed route that you’ve followed along a roadtrip. Where have you stopped, what did you see, how did it make you feel? Map your journey, that’s what the roadtrip is about anyhow.

Review - A catch-all for events, media, and tools relating to the Great American Roadtrip. Maximum of 1000 words, 0-5 images

OPEN CALL FOR ABSTRACTS (200 words max)

Submit your abstract (max. 200 words) by March 6th, 2026, SUBMIT HERE

Selected authors will be notified by March 20th, 2026. Full submissions will be due by April 3rd, 2026.

Issue will be published in the Spring of 2026.

All abstract submissions must be in English (final contribution will be in English only).

Authors are responsible for the use of non-original drawings, photos, and other materials in advance.

When Road trip Turns to Festival

A meadowlark let loose a piece of plaintive song in the mist, and a recognition moved in my memory as if I’d been here before.

William Least Heat-Moon, Blue Highways page 23

One thing nearly everyone can relate to is the effort that goes into the road trip playlist. Whether it was in the version of a cassette, burned CD, or compiled on Spotify, it sets the tone for that entire journey on the open road. What better way to celebrate this Great American Road trip than to follow the music itself down the highway. From all corners of the country, musicians make their way to the Tree Fort Music Festival in Boise, Idaho. Local architecture Design Build students embellish the streets with their creative pieces. Boise makes a welcoming stop for the musicians that spend a significant amount of their time on tour. We invite students, musicians, and attendees to share their collective festival experiences as well as your road trips to the venues.

Places With Nothing Left to See

Just above the legal maximum, off they went, those people who took no chances on anything—including their ideas—getting away from them. After all, they read the papers, they watched TV, and they knew America...

William Least Heat-Moon, Blue Highways page 236

America used to stop. Gas stations, diners, rest stops, and roadside attractions asked nothing but time. Directions came from strangers and a sense of place grew from standing in it. Now the destination beats us there: the image, the map, the rating. Experience comes already processed

Dead on Arrival

I walked around what was left of the streets of the ghost town: a stone fountain, a few fireplugs, four rock buildings. A monument out here in the isolation made some sense, but not a town...

William Least Heat-Moon, Blue Highways page 264

Off the main routes—the highway gathers what the interstate abandons. Things like grain elevators standing tall but empty, a weigh station long past its last inspection, a fruit stand with its tables collapsed inward … structures that once served a purpose are now markers for what has been left behind. How could these forgotten structures become places to stop at once again? This is a call for proposals to repurpose the forgotten.

! SLOW DOWN !

Instead of insight, maybe all a man gets is strength to wander for a while. Maybe the only gift is a chance to inquire, to know nothing for certain. An inheritance of wonder and nothing more.

William Least Heat-Moon, Blue Highways page 240

Americans have never ceased to move. The Great American Road trip continues the lineage of discovery, tracing a map of motion across geography and identity. The interstate promises speed, not wonder. What does it even mean to travel if we’re only focused on the destination?

We invite you to revisit the American road trip not as a route to nowhere. but as a space of reflection, memory, and most importantly journey. What happens when we slow down — when we see the road itself as landscape, as story, as shared experience?

Circulatory Americana

The future should grow from the past, not obliterate it.

William Least Heat-Moon, Blue Highways page 382

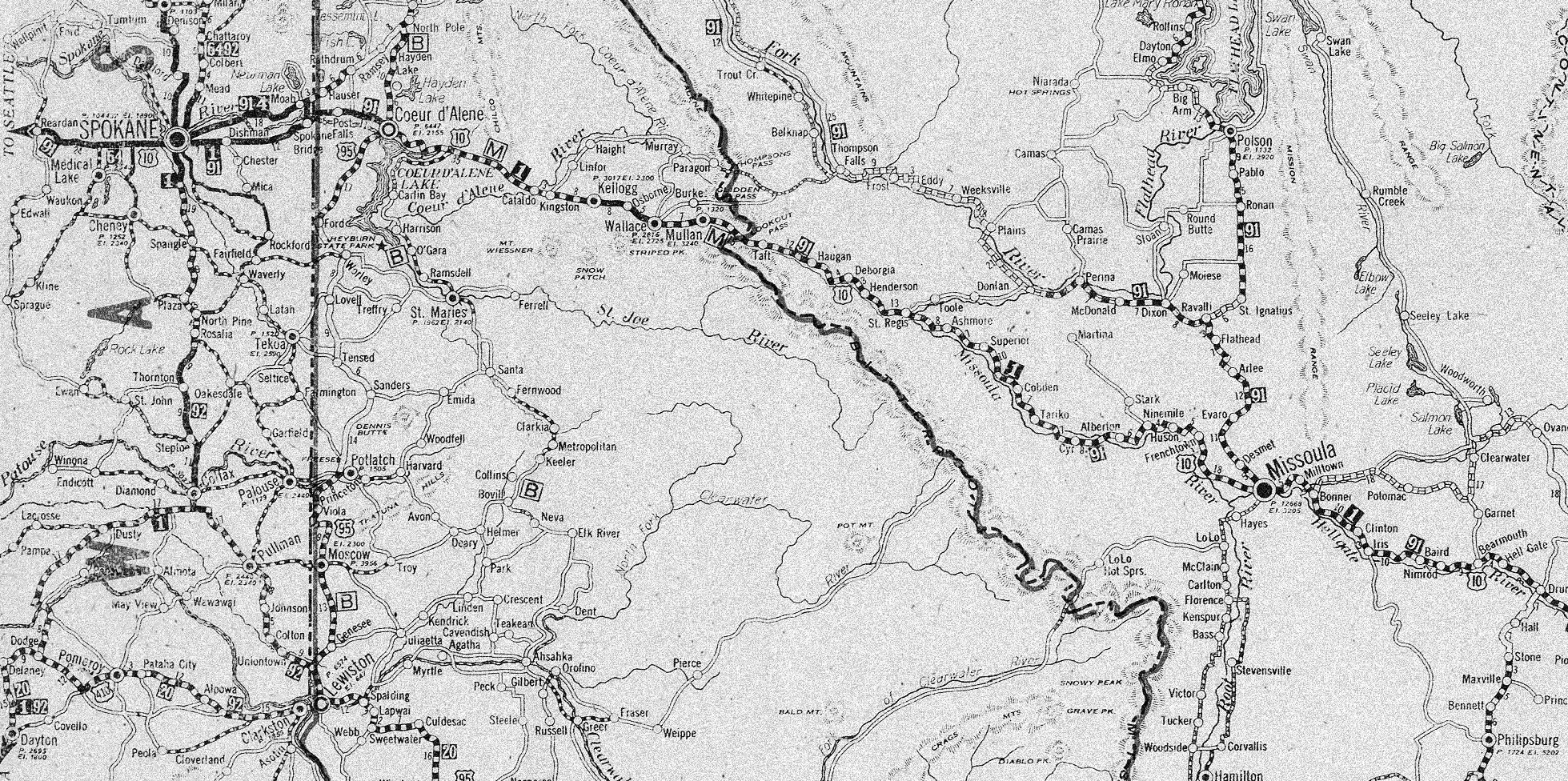

For the better part of seventy years, America’s circulation has depended on massive arterial infrastructure: the highways and interstate that sustain cities and towns. As these systems age, the veins of the nation began to varicose; communities that once thrived along forgotten routes wither into obscurity, bypassed by the promise of speed and scale.

At the same time, local streets are transforming — in some places toward connection and resilience, in others toward congestion and decay. How does the built environment adapt when the nation’s circulation falters? Can new forms of connection emerge from what has been severed or left to decay?

Red, White or Blue?

The main routes were red and the back roads blue. Now even the colors are changing.

William Least Heat-Moon, Blue Highways page 11

Our infrastructure is coded in color. Everywhere you travel, red, white, and blue trace the nation from coast to coast. We invite you to explore where these colors cross and blur. How do you move between them? Follow the color, follow the feeling, follow the road. Let your itinerary map the spaces between red, white, and blue.

The Great Outdoors

Roadside wildflowers—bluebonnets, purple winecups, evening primroses, and more—were abundant as crops, and where wide reaches of bluebonnets covered the slopes, their scent filled the highway.

William Least Heat-Moon, Blue Highways page 134

America’s great outdoors is under immense pressure from extraction, neglect, and privatization. From the forests of Idaho to the mountains of Appalachia, the outdoors holds inheritance and loss. Its a reminder that preservation is a continual act of care, not nostalgia. How might architecture respond to the limitlessness of the land as it gives way to irresponsibility and disrepair? How might we reinvigorate our collective responsibility to defend America's outdoors?

O’ To Realize Space!

The plenteousness of all, that there are no bounds,

To emerge and be of the sky, of the sun and moon and flying clouds, as one with them.

William Least Heat-Moon, quoting Walt Whitman, Blue Highways, page 189

Traveling through the Midwest, you will find yourself staring into wide horizons and appreciating the emptiness of the land. A humbling sensation these spaces provide is profoundly difficult to harness through the built environment. The single-family home with a vast yard does nothing but stifle such a sensation. We invite you to explore how sublime, humbling buildings might be integrated into the roadside landscape without suppressing the sensation.

Nobody is Here to Stay

No matter how you build it, the motel remains a haunt of the quick and dirty... Who ever heard the returning traveler exclaim over one of the great motels of the world he stayed in? Motels can be big, but never grand.

William Least Heat-Moon, Blue Highways, page 316

Along the road trip, there are two certainties: gas stations and motels. Both are utilitarian yet different. The gas station is a quick affair, built for a car-traveling America. Motor-hotels are not much different. The elusive motel clients are only there for a night, traveling different directions for separate reasons. They are only connected by the motel they stay at, and when they leave, they are anonymous once again. The result of these practices is a liminal realm simultaneously neutral and universal. When stopping for a few minutes, what is there to impact the weary traveler?

Are We There Yet?

Ten thousand miles of blue highways had wearied me, especially after driving the last three hundred of them in rain. I wasn't tired of traveling, and I had no reason to go home, but I wanted to put the wheel aside, to get off striped pavement for a few days.

William Least Heat-Moon, Blue Highways, page 304

Barreling down the highway at over sixty miles an hour, the world pulls away, and one faces an expanse of road that stretches into the distance. Here, the landscape stretches out before the car. Mountains and trees in the distance become a familiar sight, and there is only less and less to look at. Regardless, focus is on the road and its long route. When the landscape starts to lose its sense of place, where is “there?”